Digital

Image Processing

on the Mac

Bill

Majoros

June, 2007

For 99.9% of my photographic work I process the digital image

files

using only the built-in software that shipped with my Apple Macintosh

computer. Similar software is available cheaply or for free for Windows

and Linux systems (I switched from Linux to Mac at about the same time

I took up photography). Although I do have a copy of Adobe's Photoshop,

and have used it a (very) few times to remove vignetting from images

taken through my astronomical telescope,

I've found that tinkering with Photoshop just takes too long. Since I

often take hundreds or even thousands of photos during regular weekend

shoots, I simply don't have time to apply complex processing to all of

my photos.

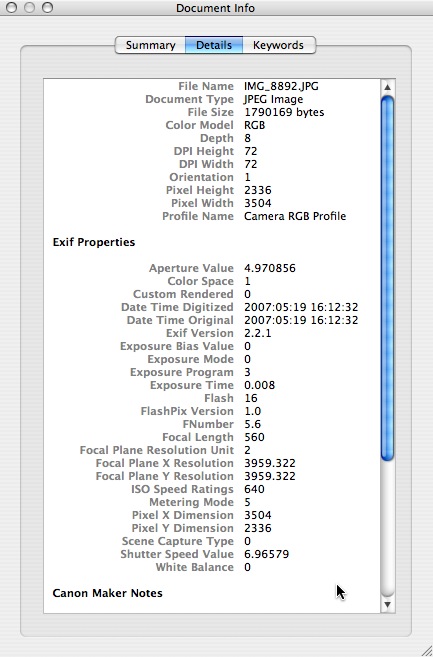

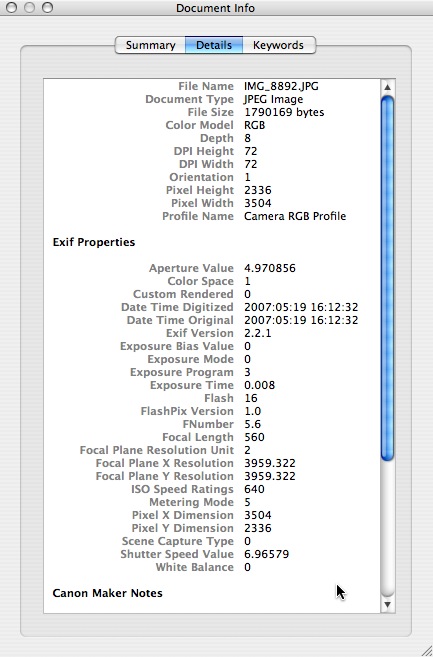

The Mac program I use is called "Preview", and ships as a standard part

of the OS X operating system. Although this program is generally

only used as a basic utility for viewing image files, it has some very

useful functions, such as the "Document Info" window, which reports

various figures extracted from the image's EXIF data:

From this I can deduce the ISO setting (560 in this case),

the exposure time (0.008, or 1/125 sec), the aperture (f/5.6), the

focal length (560mm = 400mm x 1.4, taking into account the

teleconverter I was using), and the exact time that I took the photo

(4:12pm, May 19, 2007).

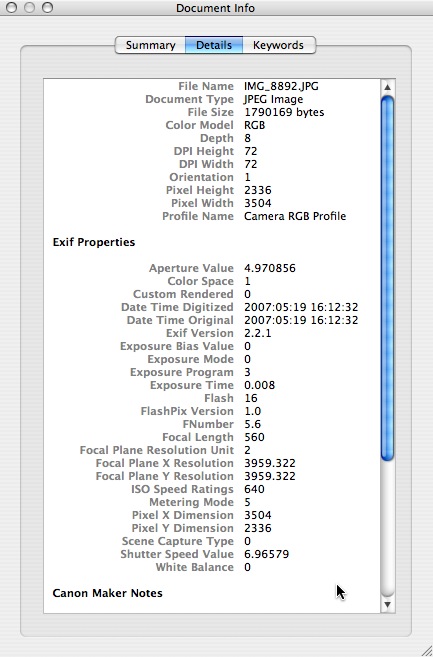

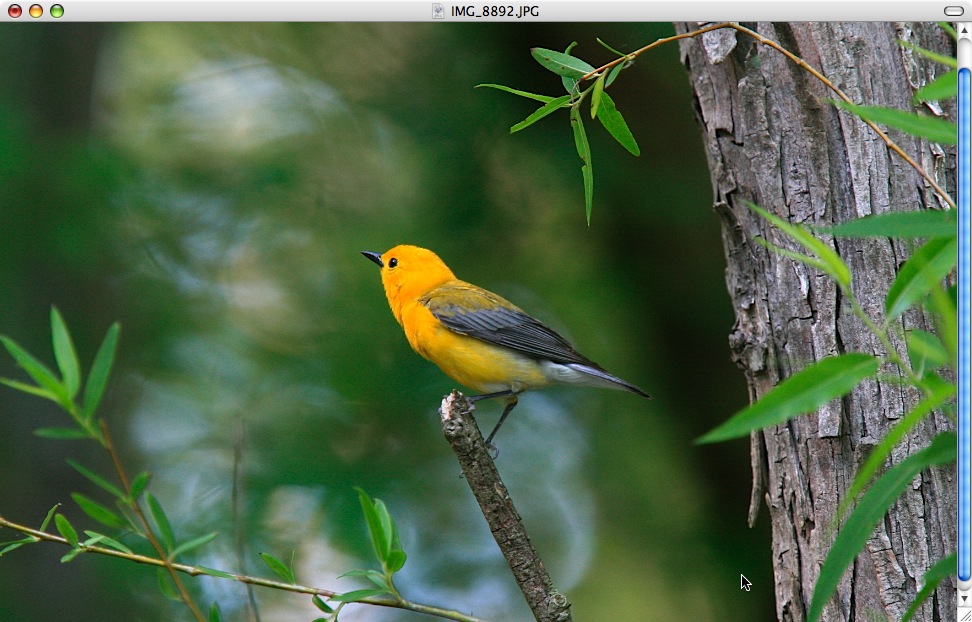

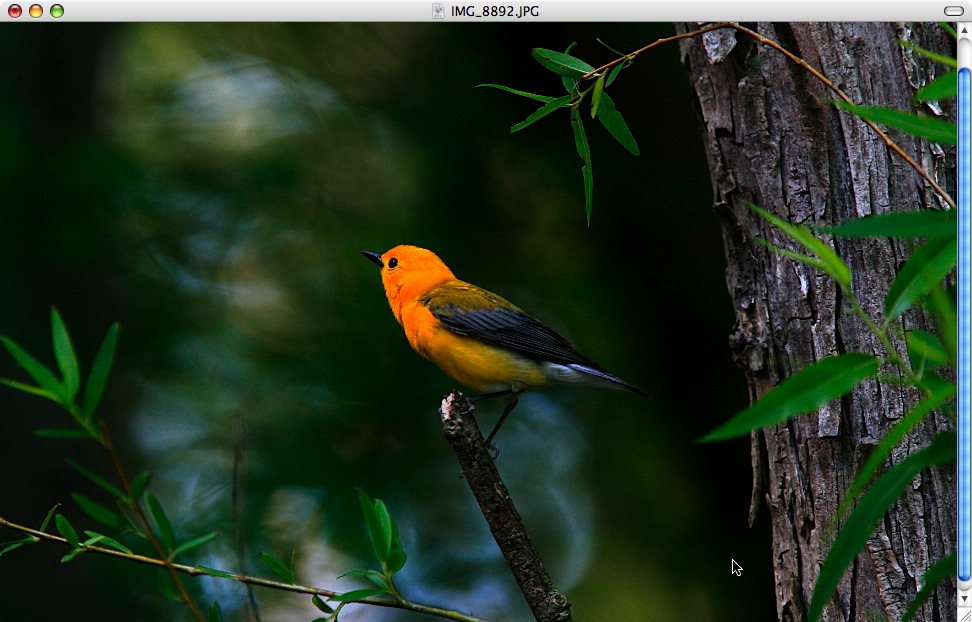

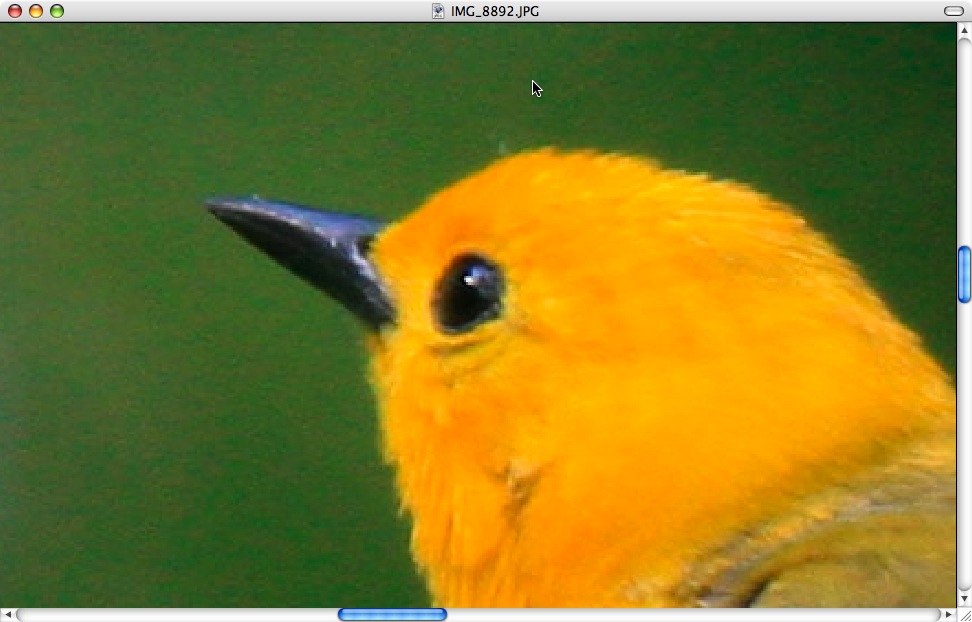

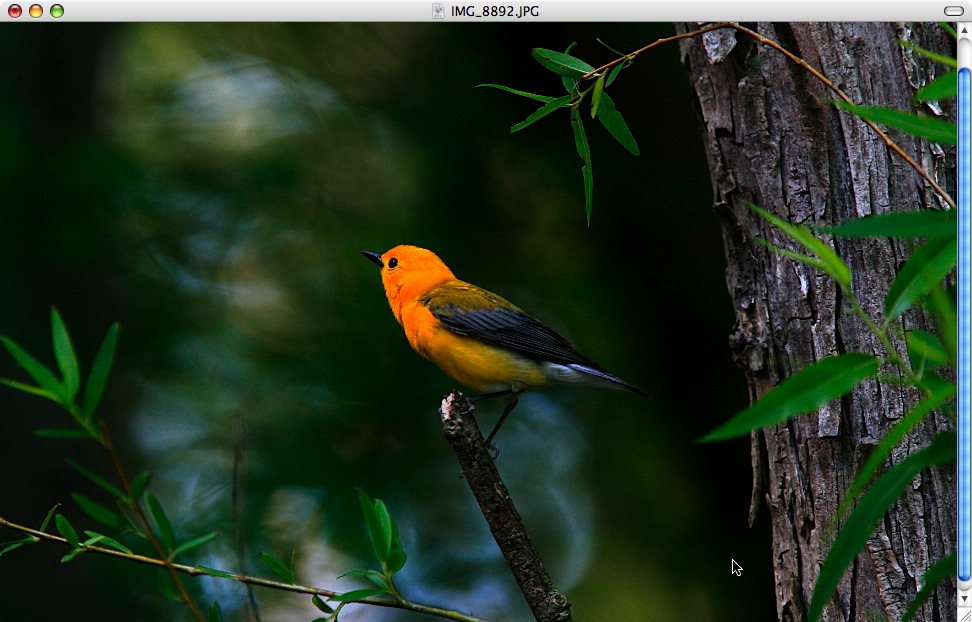

Since "Preview" is the default image-viewing application in Mac OS X,

all I have to do to launch the program is double-click the image file

in the file browser. Preview starts up in under a second on my

computer. It automatically displays the image in its native pixel

resolution. As you can see from the image below (notice the

scroll bars), at its native resolution the image will not fit on my

screen, so I can look at only a small window of the image at a

time. Here I've centered the window on the head of my subject --

a Prothonotary Warbler:

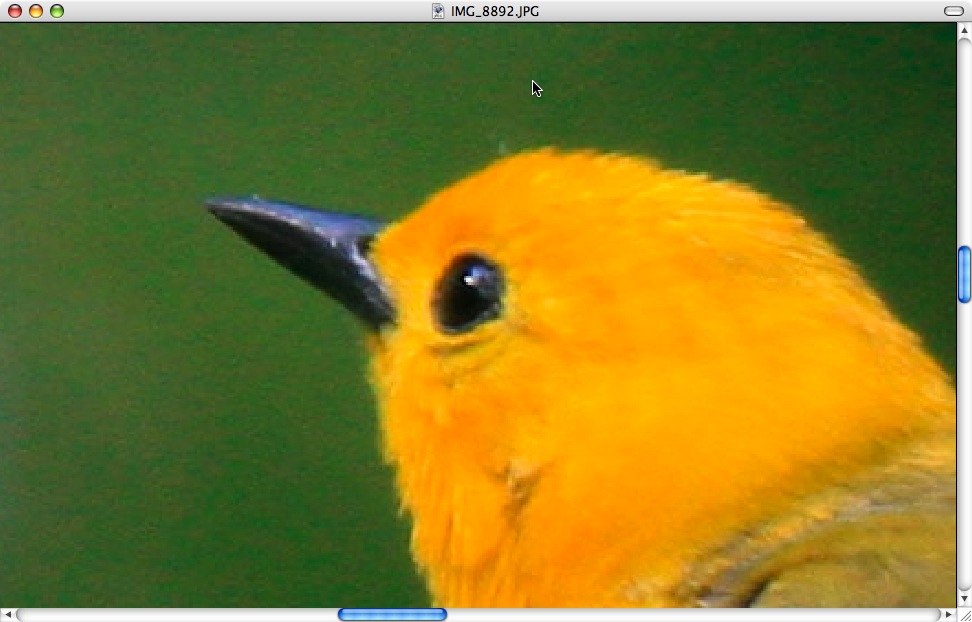

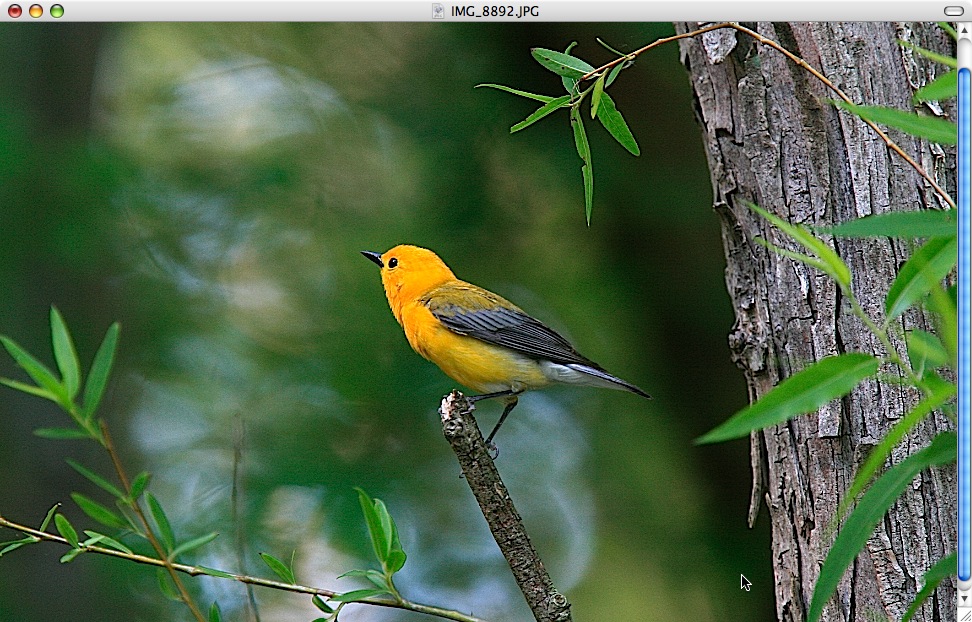

With a simple key combination I can quickly (i.e. in 2

seconds) reduce the image so that the entire bird fits on my screen,

while at the same time also reducing the "pixelation" of the image so

that it appears smoother (though it is, admittedly, rather blurry at

this stage):

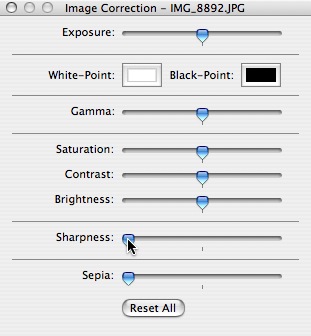

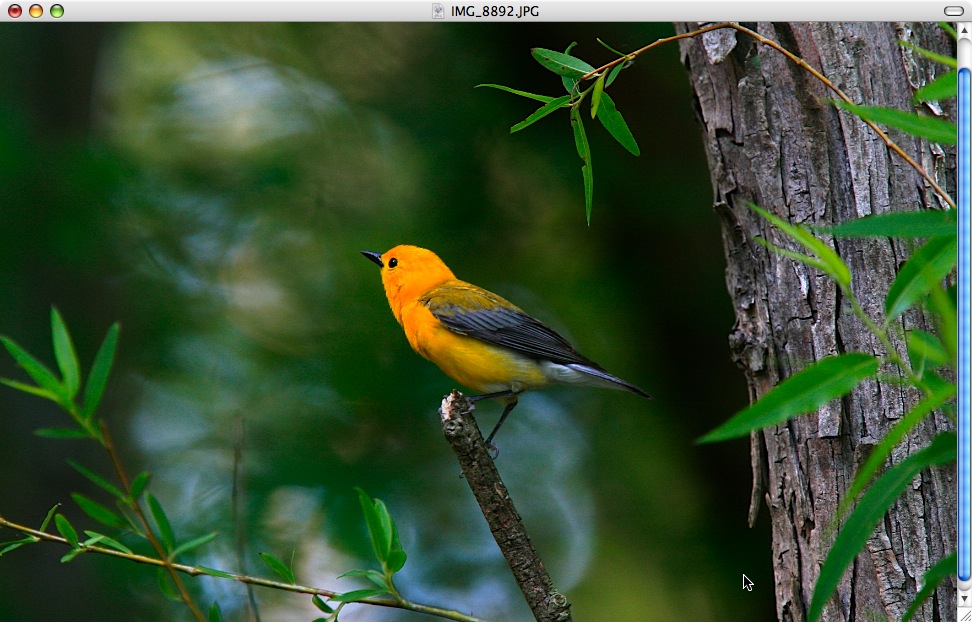

Now I can use the "Image Correction" feature of the program

to very quickly enhance the photo. The Correction tool consists

of 7 sliders, though I only ever use 3 of them:

(1) Sharpness,

(2) Gamma,

(3) Saturation.

The wonderful thing about this tool is that I can immediately slide the

controls back and forth and in a matter of seconds find the ensemble of

image settings which are most aesthetically pleasing to my eye:

In rare cases I've also used the "White-Point" feature to

correct for extreme color aberration, but I almost never need it.

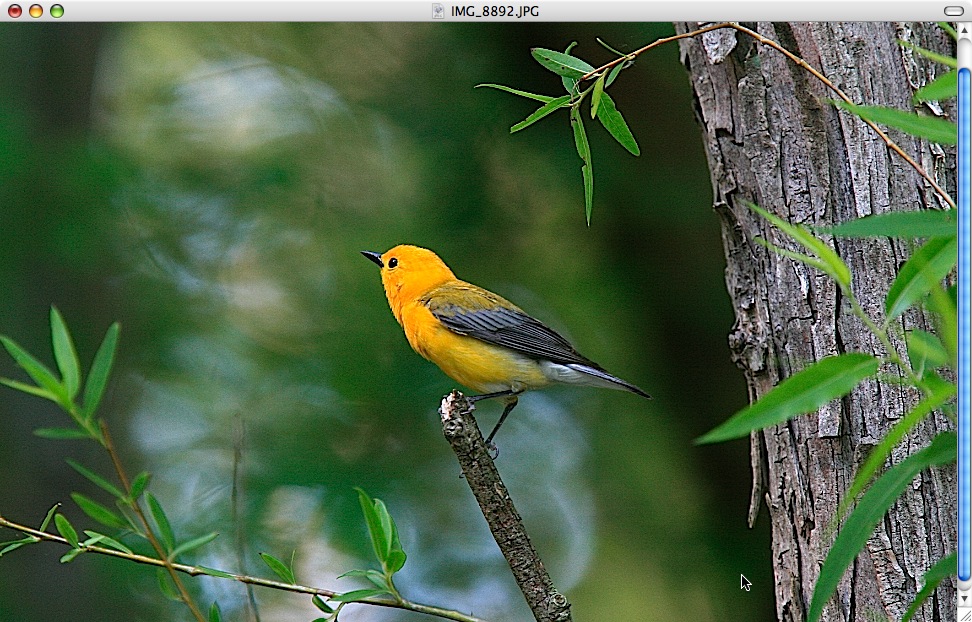

To see the effect of the Sharpness slider, observe what happens when I

slide it about 20% of the way from its default "zero" setting:

If you compare this image to the previous one, you'll see

that there is a very slight difference in sharpness (you may have to

scroll back and forth between the images several times to see the

difference, since it's a bit subtle).

The sharpened image should seem to be slightly more "in focus" than the

preceding image, and indeed, this feature can sometimes correct for

very slight focusing

errors in images, though it cannot magically turn a completely

out-of-focus image into an in-focus one. Overly agressive use of

the "Sharpness" slider results in fairly obvious defects in the

resulting image:

While the above image may at first seem more pleasing in its

greater sharpness than the preceding image, if you look at it long

enough you will see that it is much grainier, and is in some ways

reminiscent of photography published in cheap books from the 1970's and

early 1980's (and in the dirt-cheap editions regularly placed on

clearance at Border's...).

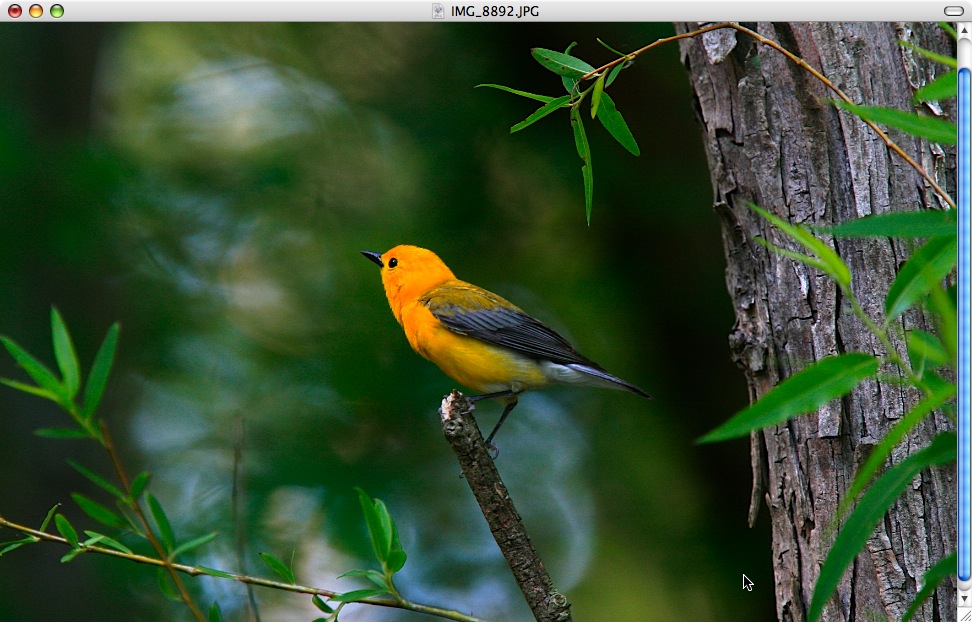

Next, let's see what happens when we twiddle the "Gamma" slider:

Here I've increased the "Gamma" by a modest amount, and you

can see that the image has, overall, become somewhat darker, though the

bird remains bright. The gamma metric incorporates elements of both

brightness and contrast, and also tends to affect saturation

(somewhat). Apart from the Sharpness slider (which I almost

always tweak at least a tiny bit), this is the main slider which I use

in the Preview program. I never, ever, touch the Brightness

slider (never!), very rarely

touch the Contrast slider, and only tweak the Saturation slider when

Gamma leaves me wanting still more color.

Gamma is a truly wonderful thing. Since it automatically controls

for both brightness and contrast, a quick exploration of the slider's

range gives a fairly accurate indication of the image's potential along

these two parameter axes. The following image was obtained by

pushing the Gamma setting to the extreme:

Keep in mind that all of this twiddling with my mouse cursor

has taken no more than about 15 seconds -- which is literally all I can

afford when processing the thousands of images taken during my most

recent weekend jaunt.

At this juncture I should note that currently I only prepare

my images for web distribution, and only very rarely print them out

onto photo paper. Thus, my methodology is geared entirely toward

optimizing my images for display in the web browser.

To that end, I find it extremely useful to adopt a WYSIWYG approach to

image preparation -- that is, What

You See Is What You Get (=WYSIWYG).

Since I prepare my web pages using my own custom software, I know that

the (manually processed and cropped) images will be served in their

full resolution to web browsers. Thus, I utilize this knowledge by

trying to capture the image in the exact resolution which seems (to my

eye, at least) optimal for viewing on a computer screen.

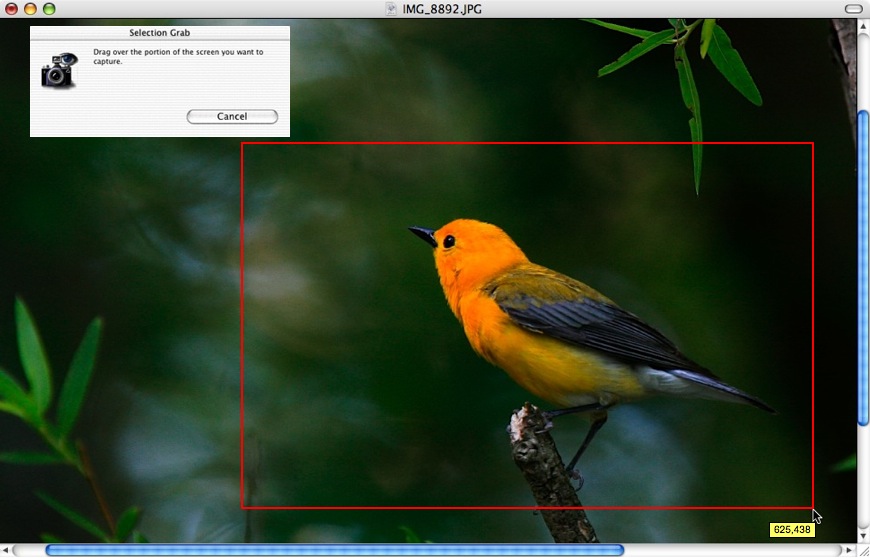

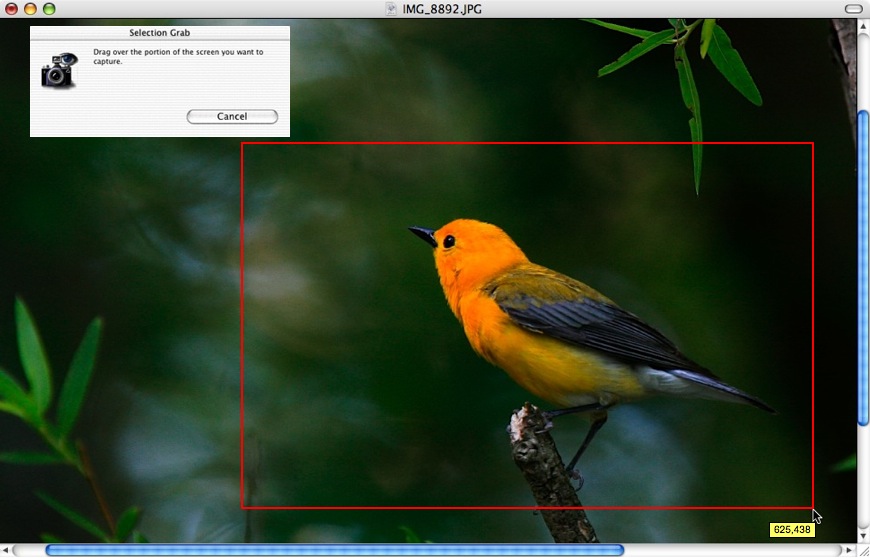

I do this by using another built-in program in Mac OS X -- the "Image

Grab" utility, which is shown in action below. Using this tool I

can choose the cropping which places the subject and its surroundings

in the most aesthetic positioning within the resulting image. The

selection tool creates a new image file containing exactly the image I selected

on-screen, so that at the time I perform the selection I know exactly what the resulting image

will look like when viewed later via the web:

Other operating systems have their equivalent. The important

point is that I optimize the image for viewing on my computer screen,

then capture the image exactly as I see it, and serve that image over

the web at the same resolution, without any image resizing (except

where over-ridden by rogue web browsers...). This is important, because

an image which appears exceptionally sharp on my screen can look quite

blurry when it is resized using a standard image scaling algorithm.

I take this philosophy to the extreme: when preparing my images I never

scale them by any non-integral factor. I only zoom in or out by a

factor of 2. In this way, mathematical rounding errors by the

imaging software when pixels are re-mapped during a scaling operation

are minimized, so that maximal sharpness is retained during scaling.

Since the cropped version of the image that I publish to the web is

stored in a new image file, I leave the original image from the camera

untouched -- that is, I don't save the changes to the original image

file. That way I can always re-process the original image

later -- for example, if I want to print out a full-frame version on

photo paper.

In terms of the actual distribution of images over the internet, there

are a number of web sites which provide different services at different

prices (some free, though generally with limitations). I prefer

to run my own site with my own custom software. This way I can

retain complete control over any transformations which are to take

place before the viewer sees the image on his or her screen.

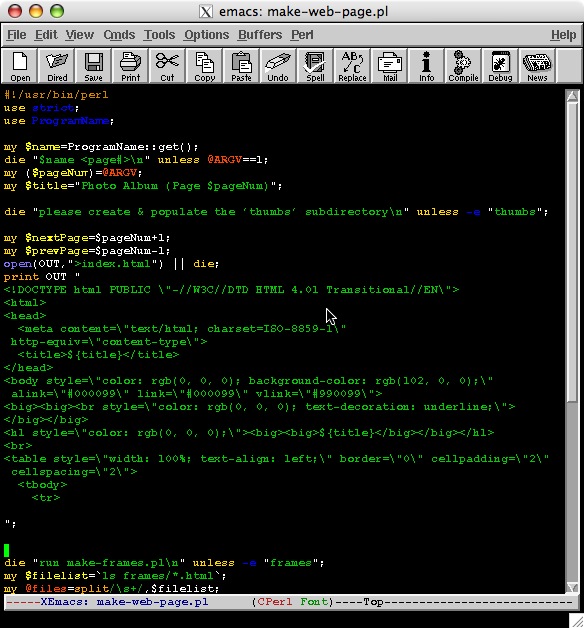

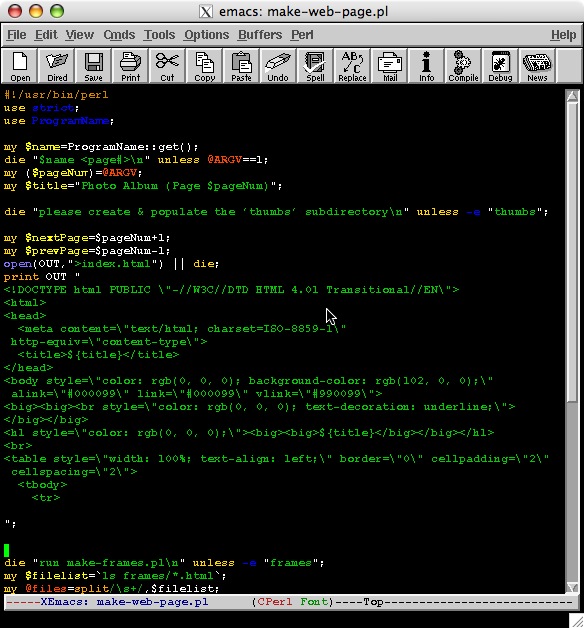

The software I use is very simple, and is written in the

freely-available language Perl.

I edit my software using the free software XEmacs:

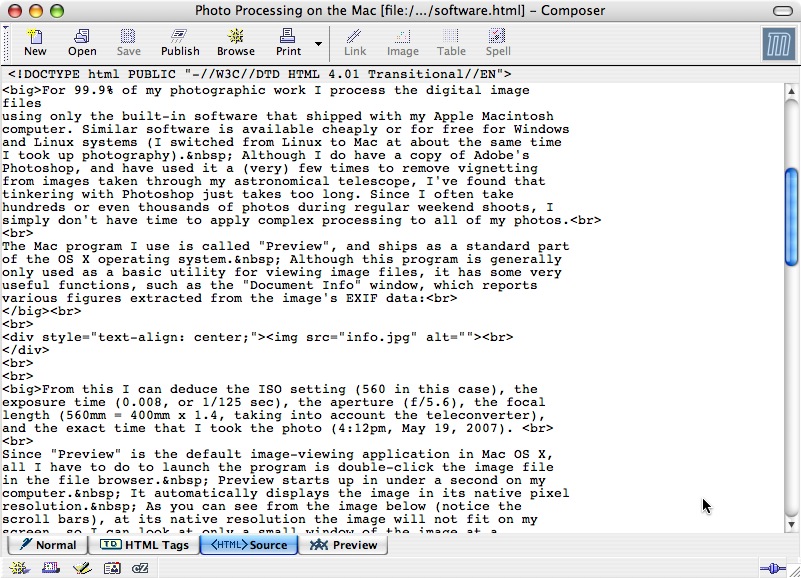

The software I use automatically generates thumbnail images,

slideshow sequences, and the main HTML file for each photo album. To

tweak the appearance of each page (i.e., to customize the colors and

accompanying text for the thumbnail index), I use the free software

suite Mozilla:

Once I have a new photo album looking exactly as I like it on

my own computer, I upload it to my web site using the UNIX "ftp"

program. For serious distribution of photos (i.e., lots and lots

of them), managing your own website can be highly effective, both in

terms of the monetary costs and the flexibility thereby afforded.

My web hosting provider, IPOWERWEB,

provides an obscene amount of storage space (many Gigabytes -- enough

to store many thousands of photos) and full customizability for about

$8 a month.